The “Study for Suprematist Cross” by Kazimir Malevich stands as a testament to the preparatory, behind-the-scenes work that often goes unnoticed in an artist’s journey. As an early stage composition, its sketchy straight lines and rudimentary geometric shapes captured the essence of what Malevich sought to achieve: a world of pure feeling and perception. Created as a foundational step before the final painting, the drawing offers invaluable insights into Malevich’s thought process. It’s a glimpse into his sketchbook mentality where visual ideas and compositions came to life before the commitment of oils, a process that, fortunately, preserved many of his study drawings that could have been lost to time.

In 1927, this preliminary study culminated in “The White Suprematist Cross,” a work characterized by its geometric forms that transcend mere shapes to represent Malevich’s belief in white as the embodiment of infinity and a utopian world of pure form. Measuring 68×88 cm, this artwork underscores Malevich’s Suprematist theory – a groundbreaking philosophy that champions the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts. It is noteworthy, however, that while the “Study for Suprematist Cross” and “The White Suprematist Cross” share a conceptual lineage, they stand as distinct, separate artworks, each holding its unique place in the annals of art history.

Diving deeper into the realm of Suprematism, a movement pioneered by Malevich in the tumultuous backdrop of early-20th-century Russia, one discovers an art form that bravely challenged conventions. Geometric forms like the cross emerge as motifs, not just as mere shapes but potent symbols of spiritual transcendence. While details about the specific interpretation of the “Suprematist Cross” might be scarce, its influence on the trajectory of modern art cannot be overstated. From shaping the Modernist art culture in Russia to inspiring contemporary abstract, minimalist, and conceptual art movements, the ripples of Malevich’s avant-garde vision can still be felt today.

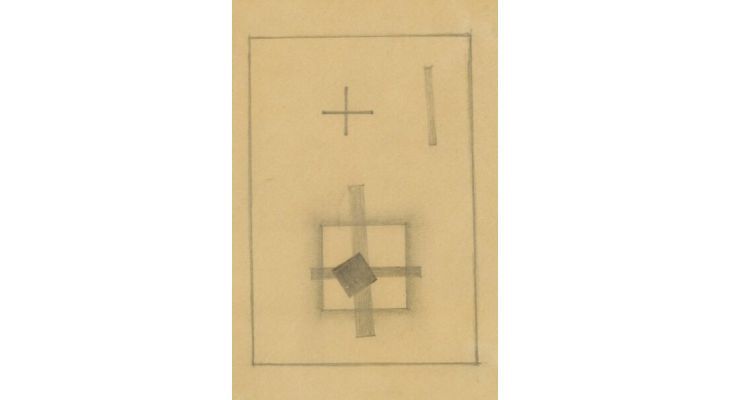

Artist Malevich is most famous for his contributions to the Suprematist movement. Despite the simplicity of some of the compositions, he would still require good levels of study in preparation for the final paintings, one of which is displayed here.

The image in front of us here is entirely simple, and typical of the Suprematist movement. There is a small border which encapsulates the composition within the larger piece of paper, and then inside we find a whole series of squares, lines and crosses. The crosses would suit Malevich’s abstract style perfectly, but they also delivered a religious tone to his paintings which was entirely appropriate considering its role within Russian life at the time. Indeed, the impact of Christianity is still particularly strong within parts of Eastern Europe. Malevich would continue to experiment with crosses in various arrangements throughout his use of Suprematism, but less so later on when he re-imagined this approach in the form of Neo-Suprematism. With regards this study, there is a single cross at the top, with a narrow rectangle close by. Below is a more complex arrangement with cross, square and also a bezelled border which suggests depth to an otherwise flat artwork.

The artist would have to be careful in later life as the ruling authorities in his native country became concerned about the modern style of his work. Some would be left in Germany in order to protect, whilst some of his other paintings would be seized and destroyed. Despite falling into controversy during that period, Malevich is today highly celebrated around the country and is seen as someone that Russians should be proud of and who has left an artistic legacy which is still felt today all around the world. This legacy is underlined by the number of exhibitions of his work that continue to pop up all across the continent, as well as further afield such as in the US too.

Malevich would spend time in the company of a number of other highly significant artists during his career, most notably Marc Chagall. This Belarus-born painter would later relocate to France but came from a fairly similar background to Malevich and is another example of this impressive culture found within this part of Europe. Some of Chagall’s most famous paintings included the likes of Blue Violinist, La Mariee and I and the Village. His work differed considerably from that of Malevich, but they shared similar views with regards the importance of modern art and how it should be allowed to flourish alongside more traditional methods. The term Russan Avant-Garde refers to a wider group who shared these views and worked together in order to build support for some of these modern art styles within a relatively traditionally-minded nation. Ultimately, some would eventually feel it necessary to permanently move abroad, whilst others stubbornly remained, hoping to force change from within.