Kazimir Malevich’s Head of a Peasant (1913) is a small painting that embodies a pivotal moment in the evolution of modern art. At just 23 x 22 centimeters, this modest portrait nonetheless contains the rupturing forces that would shatter centuries of artistic tradition. The fractured planes of the peasant woman’s face signal Malevich’s break with visual mimesis, foreshadowing his imminent invention of the entirely abstract Suprematist style. Standing rapt before this canvas at the Museum of Modern Art, I glimpsed the raw creative energy that launched painters into unmapped territory, searching for new ways to distill feeling into line and color.

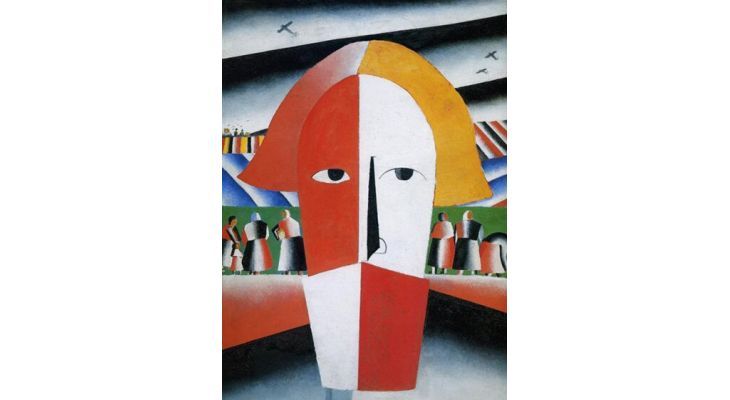

Rendered in Cubo-Futurist style, the face emerges from interlocking planes of unmodulated color. Jagged triangles outline the eyes and nose, conveying a sense of fracture and dissolution. The peasant stares past us with an inscrutable expression that evokes alienation and dislocation. Malevich conveys his subject not as an individual, but as an icon of persistent folk tradition amidst modernity’s rupture with the past. By dissolving form, he pushes toward a new artistic realm where emotion is conveyed through composition alone.

When it appeared at the Target exhibition in 1913, Head of a Peasant bewildered viewers accustomed to Impressionism. But today it is recognized as a signpost marking Malevich’s move toward abstraction. Standing rapt before it at MoMA, I glimpsed the raw creative energy that has propelled generations of artists. In Head of a Peasant, the essential DNA of modern art emerges within the interstices of paint between realism and pure abstraction.

Kazimir Malevich: Life and Art

Kazimir Malevich was born Karl Malewicz in 1878 to a Polish family near Kiev in what is now Ukraine. His parents moved frequently when he was a child, and young Malevich was exposed to the rural peasant culture of various regions of the Russian Empire. After studying art in Moscow, Malevich absorbed the trends of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism that were gaining popularity in Russia around the turn of the century.

In My Discovery of the ‘Nothing’, a semi-autobiographical essay, Malevich described his youthful attraction to the colors and textures of the Russian countryside: “I passed through fields of ripening rye which shone with many colors, and it was this which impressed me most. I loved the yellow wheat, the blue rye, the red rowans.” Even after his shift toward radical abstraction, Malevich would retain subtle organic references to nature, transmuted into his own visual language of shape and color.

As a young painter in Kiev and Moscow, Malevich primarily created scenes of peasant life rendered in an Impressionist or Fauvist mode. Works like The Knife Grinder (1913) and Morning in the Country after Snowstorm (1912) feature peasants rendered in bright swathes of unnaturalistic color. As he matured, Malevich became interested in recent developments in French painting, incorporating elements of Cubism and Futurism inspired by artists like Picasso, Léger and Metzinger.

Around 1910, Malevich began fracturing his figures into faceted planes and incorporating abstract elements into his paintings. 1911’s The Cow and Violin foreshadows his move toward non-objective representation, with the cow’s head rendered as a series of color-based geometric shapes against an indeterminate background. In works like Head of a Peasant (1913) and Soldier of the First Division (1914), recognizable figures of Russian peasants and soldiers are rendered in a distinctly Cubo-Futurist manner.

By 1915, Malevich had taken the final leap into pure abstraction, laying the foundations for the Suprematist movement with paintings like Black Square and White on White. Suprematist works eschewed the imitation of nature in favor of colored geometric forms floating against white backgrounds, intended to communicate pure feeling through their visual presence.

Head of a Peasant: Description and Analysis

Head of a Peasant is the transitional work of an artist progressing decisively from recognizable figurative painting toward complete abstraction. Measuring just 23 x 22 centimeters, the composition is built up through small rectangular brushstrokes that fracture the face into interlocking planes. The peasant woman’s head is covered by a colorful headscarf or babushka, a commonly identified symbol of Russian peasant culture.

The face comprises roughly triangular segments of unmodulated yellow, pink and blue color. The essential features of the face – eyes, nose, mouth, cheeks – are all flattened and delineated by harsh lines that divide the head into jagged sections. The peasant woman’s visage has little sculptural volume; her gaze is unfocused and directed past the viewer into an uncertain distance. The aggressive diagonals of her headscarf echo the dynamism of the angular facial planes.

The dissolution of the figure approaches abstraction, yet it remains possible to assemble a generic likeness of a female Russian peasant from the intersecting planes. The limited warm hues of the face are contrasted with the vibrant blues, reds, and greens patterned over the headscarf. This technique demonstrates Malevich’s assimilation of the color theory principles developed by earlier artists like Gauguin, Matisse and the Fauves.

The fracturing of form reflects the pervasive influence of Cubism during this period. Yet the lurid colors and angular lines produce an overall effect closer to Futurism’s visual language, which aimed to capture the energy and dynamism of modernity. The work seems suffused with violent internal motion; one could almost imagine the head as a mechanical object captured in freeze-frame. The off-kilter angle is dramatic and disorienting, another Futurist trait.

Malevich’s peasant subject was likely more conceptual than real; she can be read as an allegorical symbol of persistent folk tradition amidst the onrush of technological modernization. Yet her fragmented features show the human form beginning to break down and dissolve. The mental state of the anonymous peasant woman, coupled with the unnatural palette, gives the work an undertone of anxiety and alienation. The peasant here seems a puzzled observer trying to comprehend her radically shifting world.

Head of a Peasant: Reception and Legacy

Malevich first exhibited Head of a Peasant in 1913 at the exhibition Target in Moscow, alongside works by fellow avant-garde artists like Tatlin, Filonov, and Goncharova. Contemporary viewers were perplexed by Malevich’s esoteric blend of representation and abstraction. But over subsequent decades, Head of a Peasant was rightfully acknowledged as an essential milestone in Malevich’s evolution toward a completely non-objective style.

Today, the work is rightly praised for its historical significance as a harbinger of abstraction and its demonstration of Malevich’s original visual language. The painting forms part of MoMA‘s permanent collection in New York along with many seminal modernist pieces. It has been included in exhibitions of Malevich’s oevre at both the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Tate Modern in London.

Unlike some of Malevich’s more extreme abstractions, Head of a Peasant retains an approachable humanistic element through its evident subject matter. The enigmatic stare of the peasant woman draws an emotional response from the viewer. Yet the total fracturing of form signals Malevich’s belief that art must abandon objective representation to attain a higher reality.

For scholars and critics, Head of a Peasant demonstrates Malevich decisively breaking from his earlier peasant genre works toward the completely abstract idiom of Suprematism. It has been extensively analyzed as a harbinger of the visual philosophy Malevich introduced with paintings like Black Square just two years later. Head of a Peasant remains one of Malevich’s most famous Cubo-Futurist compositions, and an essential part of telling the story of his artistic evolution.

Malevich’s Influence on Modern Art

While less notorious than some of his later abstractions, a work like Head of a Peasant shows Malevich already forging a highly original style and visual language. After finally being exposed to the innovations of Picasso, Braque and others in Parisian journals, Malevich absorbed their discoveries and pushed them dramatically forward.

The fractured but recognizable face of the female peasant seems to gaze ahead in time at the radical artistic landscape Malevich would soon unveil. Head of a Peasant represents a pivotal stage in the dissolution of objective reality that would open the door to entirely new ways of constructing art.

Of course, Malevich’s Suprematist works went on to have an enormous impact on the course of 20th century modernism. The abstract vocabulary of floating, colored shapes influenced Russian avant-garde movements like Constructivism, as well as the Bauhaus-affiliated experiments in Germany. Malevich’s pared-down visual language would inspire generations of abstract artists from Mondrian to Rothko to Frank Stella.

Today, Malevich is acclaimed as one of the single most influential pioneers of abstract art. It’s possible to draw a line from the fractured but recognizable face of Head of a Peasant to thousands of subsequent abstractions that abandoned representation entirely. The work’s raw painterly energy and plastic dynamism point directly toward the aesthetic experience Malevich wanted to provoke through later works like White on White.

Malevich believed art should exist independent of reality, as an end in itself. The forms and colors of Suprematist works were intended to function as symbols conveying universal human feeling beyond material concerns. This philosophical outlook continues to resonate, with contemporary artists like Clyfford Still adapting Malevich’s visual language to express emotion through abstract means.

While Malevich’s peasantry works have art-historical value, his drive toward pure abstraction liberated him to convey the immutable human condition through color and form alone. Like so many pivotal artists, his initial representational works contain the seeds of his later radical reinvention of his craft. A painting like Head of a Peasant shows a magnetic shift toward the abstract aesthetic dimensions that transformed modern art forever.

My Personal Encounter with Head of a Peasant

During a trip to New York last summer, I finally had the chance to view Head of a Peasant up close at MoMA. Going in, I knew the painting’s historical importance in pointing toward Malevich’s Suprematist breakthrough. But as I stood before the actual canvas, I was struck by its raw visceral power. The bright hues and violent angularity are jarring, even disturbing. The fractured face peering out seems to exist in a state of bewilderment and alienation.

Despite its modest size, Head of a Peasant looms large when viewed in person. The penetrating gaze of the peasant woman establishes an uneasy connection to the viewer across a century of artistic revolution. I found it easier to understand Malevich’s drive to abandon verisimilitude as an artistic constraint. There is a yearning toward the infinite in the pitched angles and vivid colors, reflecting Malevich’s mystical belief in art’s transcendent possibilities.

Getting to view Head of a Peasant alongside other masterpieces of the early avant-garde like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was an illuminating experience. The shared fracturing of form demonstrates the cross-pollination of ideas that fed artistic breakthroughs across Russia and Europe. Works separated by thousands of miles spoke a common visual language of abstraction, reduction, dynamism.

Standing in MoMA’s galleries, I felt immersed in the open possibilities and fervent experimentation that defined the modernist revolution. Amidst the endless reproductions of high modern masterpieces, encountering an original canvas retains an irreplaceable power. A painting like Head of a Peasant becomes most vivid when its brushwork can be examined up close, its texture and muted colors directly perceived.

Getting to observe works like this in person provides a vital link to the past, reminding us that even the most radical artistic revolutions were built up through individual gestures by working artists. The fractured planes that shocked Malevich’s contemporaries represent the attempts of an avant-garde painter feeling his way forward into new terrain. We are the beneficiaries of the creative leaps and risks taken by Malevich and his fellow pioneers of abstraction.

FAQs about Head of a Peasant and Kazimir Malevich

What is the meaning of “Head of a Peasant”?

The fractured planes and geometric forms of “Head of a Peasant” reflect Malevich’s move away from representation towards abstraction. The painting expresses his view of modern life as fractured and dynamic, and his belief that art should focus on expressing human feeling through color and form alone.

What is the significance of Kazimir Malevich in the art world?

Malevich was an extremely influential pioneer of abstract art. Through his Suprematist movement, he introduced radical new ways of making and thinking about art independent of objective representation. His ideas opened the door for countless artists to explore abstraction.

How did Malevich’s ideas about art influence other artists?

Malevich believed art should express meaning through abstract visual elements, not by mimicking physical reality. This liberated later artists to explore abstractionExpressionists, Minimalists, and contemporary artists have all been impacted by Malevich’s philosophy.

What is the legacy of “Head of a Peasant” in the art world?

As an early avant-garde work by Malevich, “Head of a Peasant” is recognized as a crucial milestone in his progression toward pure abstraction. It demonstrates his evolving visual language and philosophy prior to his Suprematist breakthrough.

Why does the peasant woman appear slightly off-center in the composition?

The asymmetrical composition likely reflects the influence of avant-garde approaches like Cubism and Futurism, which embraced dynamic angles and perspectives. It may also symbolize the sense of disorientation sweeping early 20th century society.

What meaning can be drawn from the peasant woman’s unfocused gaze?

The woman’s indistinct stare and seeming detachment from the viewer evokes a feeling of alienation. This underscores Malevich’s view of modern citizens as disconnected from nature and tradition.

Conclusion

In Head of a Peasant, Malevich developed his distinctive variant of the Cubo-Futurist aesthetic that fascinated the European avant-garde. While more representational than his later Suprematism, the work embodies Malevich’s plastic philosophy of giving feeling and meaning visual form through lines, shapes and colors. As one of Malevich’s famous peasant portraits, Head of a Peasant provides vital context for understanding his progression toward pure abstraction.

Standing before the canvas at MoMA, I was able to appreciate its textures and muted hues that resist reproduction. The raw visceral power contained in its angular planes was revelatory. In person, Head of a Peasant appears as a crucial pivot point in the dissolution of recognizable reality that opened the door for abstraction. As an admirer of modern art’s capacity for innovation, being able to view this seminal painting was a reminder of the creative risks required to push art forward in search of new forms of expression.